- Morning Brief

- Posts

- Statins: Most Prescribed Drug With Hyped Benefits and Downplayed Side Effects

Statins: Most Prescribed Drug With Hyped Benefits and Downplayed Side Effects

Statins, one of the most commonly prescribed and bestselling drugs in history, have shaped Western society’s approach to treating heart disease.

(Illustration by The Epoch Times, Shutterstock)

Statins, one of history’s most commonly prescribed and bestselling drugs, have shaped Western society’s approach to treating heart disease.

Akira Endo, a Japanese-born biochemist, discovered statins from mold. His research garnered the attention of pharmaceutical companies, aiming to find a compound that could effectively lower cholesterol—the assumed cause of heart disease. Merck ultimately obtained samples of the drug and was “astonished at the potency,” Mr. Endo said in his review, spurring the pharmaceutical company to develop its own statin.

In 1987, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Merck’s lovastatin, the first commercial statin.

At the same time, questions began to accumulate about this wonder drug.

Statin Benefits: Same Coin, Different Sides

Statins are regarded as life-saving medications because they reduce the risk of heart attacks and strokes, as asserted by numerous studies investigating their safety and efficacy. In these studies, a statistical analysis model called relative risk reduction is often employed to demonstrate drug efficacy.

However, this model can be misleading, according to Dr. Malcolm Kendrick, a UK-based physician who has published multiple reviews on cardiovascular disease and statins in academic journals.

“It’s a way of hyping benefits,” he said.

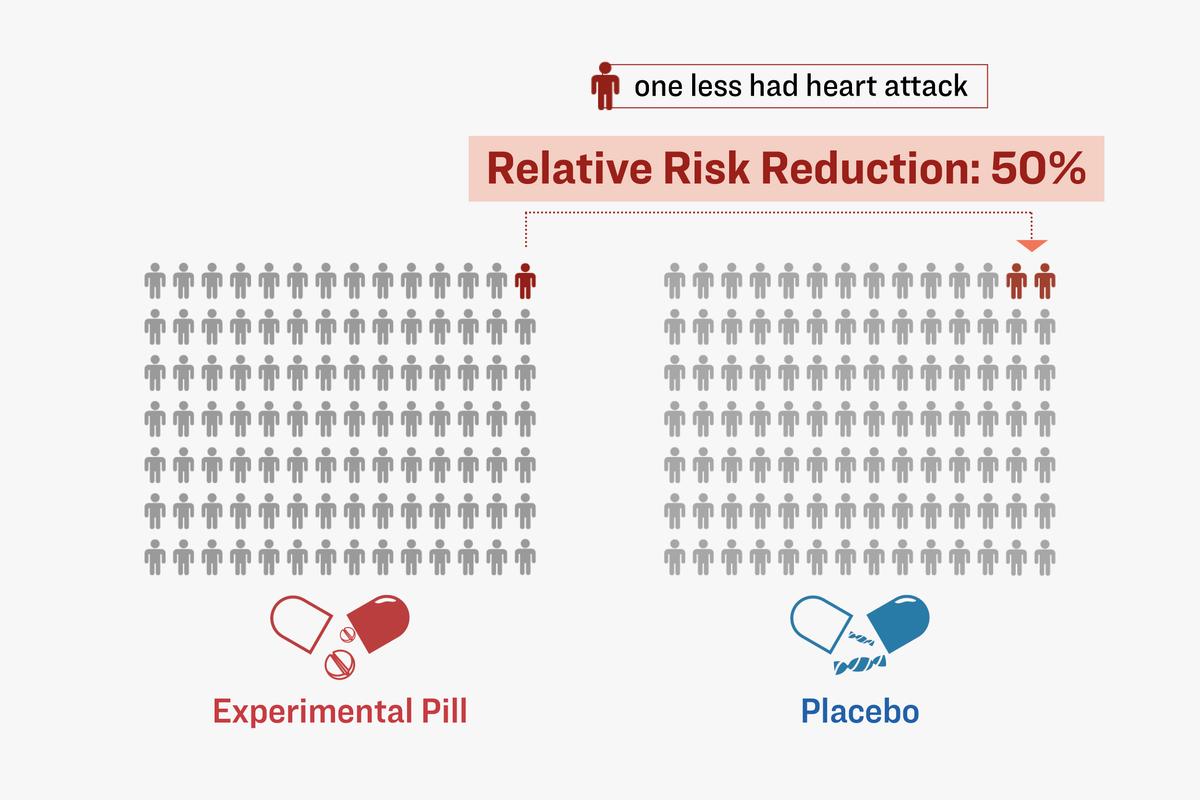

Suppose that there are two groups of 100 people, with the first group taking an experimental pill theorized to prevent heart attacks and the second group taking a placebo. During a trial time of two years, the first group experienced only one heart attack, while the second group recorded two.

Statistically, the experimental pill appears to be insignificant in its cardiovascular protection. But when the relative risk reduction is applied, the pill shows a 50 percent efficacy in decreasing heart disease as compared with the placebo, given that there was one fewer heart attack in the treated group.

Statistically, the experimental pill appears to be insignificant in its cardiovascular protection. But when the relative risk reduction is applied, the pill shows a 50 percent efficacy. (Illustration by The Epoch Times, Shutterstock)

This inflation of data spurs glowing media coverage. Reporting the results of a large 2008 study, The New York Times noted that the risk of heart attack was “more than cut in half” by statins. The study evaluated AstraZeneca’s rosuvastatin (Crestor) on 17,802 people without high cholesterol, finding about a 50 percent relative risk reduction of heart attack in the statin group.

Another study, commonly cited to exemplify statins’ robust protective effects, is a large trial investigating Pfizer’s atorvastatin (Lipitor), called ASCOT-LLA. In this case, statins were 36 percent more protective than the placebo.

However, the absolute risk reduction for both studies was approximately 1 percent.

A large trial investigating Pfizer’s atorvastatin (Lipitor) found the relative risk reduction was 36 percent, but the absolute risk reduction was 1 percent. (Illustration by The Epoch Times)

As opposed to relative risk reduction, assessing the efficacy of a drug is more accurately interpreted by using absolute risk reduction, according to Dr. Kendrick.

In a 2022 investigative report published in JAMA Internal Medicine, researchers from different countries reviewed 21 clinical studies on statins. They averaged a relative risk factor reduction of all-cause mortality by 9 percent and for heart attacks by 29 percent. However, the absolute risk reduction was 0.8 percent and 1.3 percent, respectively. The researchers noted that the absolute benefits of statins were “modest” and “should be communicated to patients as part of informed clinical decision-making.”

There’s a big difference between these two types of data, and the data that a study chooses to present could influence how people perceive the efficacy of statins, Dr. T. Grant Phillips wrote in a letter published in American Family Physician.

The Close Financial Ties

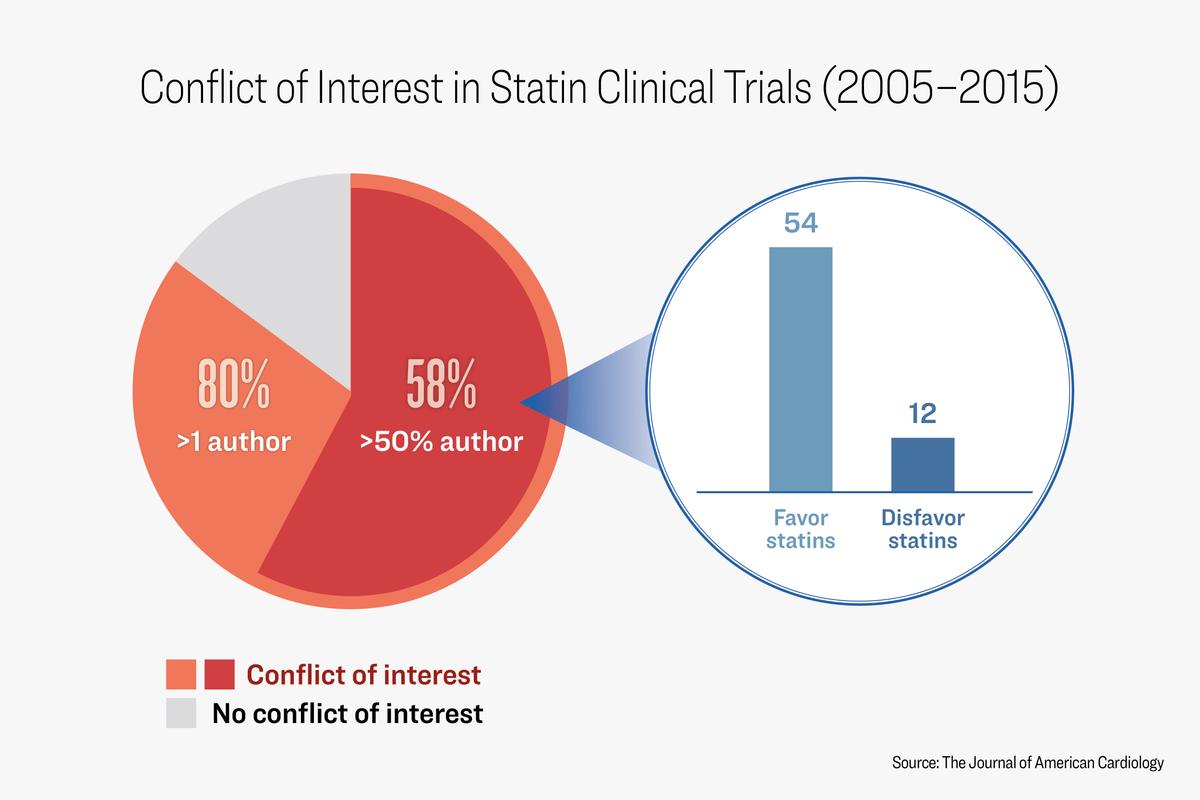

Who’s behind the studies proving statins’ ostensible benefits? It’s a crucial question to ask, according to Dr. John Abramson, lecturer emeritus of health care policy at Harvard Medical School.

“Virtually all of the major clinical trials of statins were funded by the manufacturers—when the drugs were still on patent,” he said.

In a 2015 investigative meta-analysis published in The Journal of American Cardiology, researchers reviewed all phase 2 and 3 clinical trials in a decade. They found that nearly 80 percent of the trials had a conflict of interest, and almost 60 percent involved more than half of the authors. Of these studies, 54 had favorable outcomes, and only 12 had unfavorable results.

A meta-analysis found that nearly 80 percent of the trials had a conflict of interest, and almost 60 percent involved more than half of the authors. (Illustration by The Epoch Times)

The financial ties allowed the manufacturers to design the studies and select patients most likely to benefit from and not be harmed by statin therapy. These ties also allowed the manufacturers to not compare the benefit of statin therapy to the benefit of adopting healthy lifestyle habits and to not ask prospectively about side effects, Dr. Abramson said.

The peer reviewers of medical journals who review these papers “do not have access to the actual data from the trials and must trust the usually manufacturer-supervised or reviewed manuscript as an accurate and complete summary of the trial results,” he said.

In 2013, in conjunction with the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association (AHA) updated its cholesterol guidelines, significantly broadening the criteria for determining which patients would benefit from statin therapy.

Previous cholesterol guidelines targeted the prevention of coronary heart disease, whereas the 2013 guidelines further expanded the focus to stroke and peripheral arterial disease. As a result, the number of individuals who used statins increased by 149 percent from 2013 to 2019, reaching 92 million.

Dr. Robert DuBroff, a cardiologist and retired professor at the University of New Mexico School of Medicine, reported multiple conflicts of interest among the framers of the cholesterol guidelines, including the 2013 guideline, in the Quarterly Journal of Medicine. The guidelines’ authors also failed to include multiple studies that conflicted with their recommendations, which is evidence of confirmation bias, he said.

Examples of conflict of interest and confirmation bias in cholesterol guidelines. (Illustration by The Epoch Times)

Doctors seeking to prevent coronary heart disease by lowering cholesterol are confronted by “a bewildering array of drugs, guidelines, indications, warnings, and contraindications,” Dr. DuBroff wrote.

“They expect these opinions to be comprehensive, balanced, unbiased, and unsullied by financial conflicts,“ he said. ”Unfortunately, these examples illustrate that some expert opinions fall short of these standards.”

The AHA accepts “millions of dollars from big pharma, big food, and medical device companies,” said Dr. Barbara Roberts, director of the Women’s Cardiac Center at The Miriam Hospital in Providence, Rhode Island, and associate clinical professor of medicine at the Alpert Medical School of Brown University. In 2022, the AHA received nearly $34 million from pharmaceutical companies—including multiple statin manufacturers, according to 2021–22 financial reports.

In response to The Epoch Times’ request, the AHA stated that it has strict policies to prevent these relationships from influencing the science.

“Most of our revenue—nearly 80 percent—comes from sources other than corporations,” the AHA stated.

Regarding the guidelines, it stated that “the majority of the writing committee experts [have] no relevant relationships with industry.”

Downplaying the Side Effects

Pharmaceutical companies “downplay or deny” the significance of statins’ side effects, according to Dr. Beatrice Golomb, a medical professor and statin researcher at the University of California San Diego School of Medicine. In the 2008 and ASCOT-LLA studies involving the Pfizer and AstraZeneca drugs mentioned earlier, for example, researchers reported no noticeable difference in adverse effects between the groups that received statins and placebos.

Neither company has responded to The Epoch Times’ requests for comment.

Another industry-funded meta-analysis of 19 statin trials with declared conflicts of interest found that statins only rarely “cause substantial muscle damage.”

However, some independent studies show significant differences.

The most common and noticeable side effects are muscle-related problems, with one report noting that 51 percent of statin users experience muscle pain, while a 2022 study shows that between 70 percent and 80 percent of users experience it.

Many doctors are familiar with patients reporting muscle-related problems while taking statins but misinterpret study evidence and presume that the symptoms are unrelated, “telling patients that the symptoms are merely psychological, due to age, stress, or other factors,” according to Dr. Golomb.

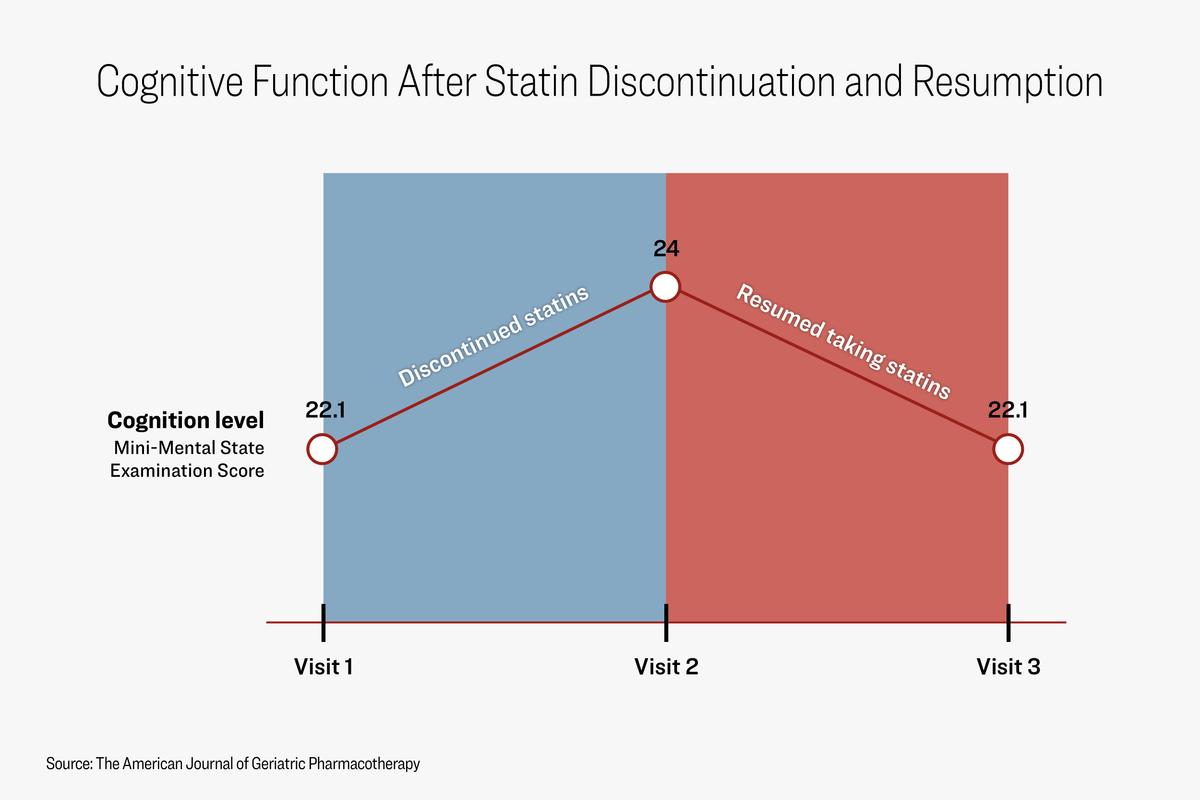

Some reports also indicate that statins could impair cognition, which has led the FDA to issue additional warnings. In one study published in The American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy, researchers tested the cognitive function of older adults with Alzheimer’s disease who were also taking statin medications. The patients stopped statins for six weeks, and their cognitive function significantly improved; after they resumed taking the drugs, their cognition digressed to its original state.

When patients stopped statins for six weeks, their cognitive function significantly improved; after they resumed taking the drugs, their cognition digressed to its original state. (Illustration by The Epoch Times)

A separate study found that among patients with early mild cognitive impairment, statin use was associated with more than a twofold risk of converting to dementia and “with highly significant decline in metabolism of posterior cingulate cortex—the region of the brain known to decline the most significantly in the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease.”

In contrast, some meta-analyses make the case for statins’ protective effects against neurodegeneration. However, as some researchers point out, these reviews analyzed statin clinical trials, which weren’t originally designed to analyze cognitive decline.

Another issue that shadows statin users is insulin insensitivity and the risk of Type 2 diabetes. A recent systematic review of 11 epidemiological studies with nearly 47 million participants found associations between statin use and decreased insulin sensitivity and increased insulin resistance—both key factors for developing Type 2 diabetes. Researchers found the increased diabetes risk was associated with long-term use. These observations weren’t ascertained in the industry-funded trials, given that many were cut short, Dr. Roberts pointed out.

There’s no corresponding financially powerful interest group that could adequately inform the public about these issues, Dr. Golomb told The Epoch Times.

The Flawed Origins

Statins’ dominance originated from the concept that high cholesterol is the leading cause of heart disease.

The battle against cholesterol began in the 1950s with a scientist named Ancel Keys. Keys hypothesized that dietary saturated fat elevated LDL cholesterol, which, according to his framework, was the root of the country’s cardiovascular health crisis. This concept is the famous “diet-heart hypothesis.” Keys launched the Seven Countries Study, an influential nutritional study, according to Jonny Bowden, a researcher and author with a doctorate in holistic nutrition.

The study analyzed the dietary habits of 12,763 men aged 40 to 59 from seven countries and found that societies that ate less dietary saturated fat were less likely to suffer from heart attacks, while those with higher intake had a stark risk increase.

However, the findings have been highly contentious among nutritional scientists, with many highlighting incongruent data, bias in country selection, and cursory observational periods.

“The study is replete with errors and misleading data,” Mr. Bowden said.

For example, it excluded countries such as Germany and France, where saturated fat consumption was high yet heart attack rates remained low.

Another error, first exposed by investigative journalist Nina Teicholz, was that Keys sampled dietary data from only 3.9 percent of the study’s participants—fewer than 500 of 12,763 people.

Ms. Teicholz also said Keys’s dietary observations of the Greek Orthodox Cretan population were skewed, given that one of his periods of observations took place during Lent. The dietary guidelines of Lent prohibit meat and dairy—foods high in saturated fat. Keys’s failure to adjust for the Lent factor was a “remarkable and troublesome omission,” according to a 2005 letter to the editor published in Public Health Nutrition.

“Clean Monday” celebrations in Athens, marking the end of the carnival and the start of the 40-day fasting period of Lent, on March 15, 2021. (Angelos Tzortzinis/AFP)

Yet these criticisms were published long after the diet-heart hypothesis had become solidified as public policy, Ms. Teicholz wrote.

“There was tremendous bias from the start; Keys had something to prove rather than a hypothesis to test,” Mr. Bowden told The Epoch Times.

The diet-heart hypothesis became the prevailing theory to shape U.S. Dietary Guidelines, which dictate the food served in school, military, and hospital cafeterias. The guidelines also play a significant role in educating medical professionals about nutrition. Ninety-five percent of the advisory committee members for the 2020–25 Dietary Guidelines were found to have conflicting interests with the food and pharmaceutical industry, according to a report published in Public Health Nutrition.

The relationship between saturated fat and cholesterol appears to be much more nuanced than that its causative.

The ‘Bad’ Cholesterol Myth

One surprising 2017 study revealed that people who consume coconut oil—94 percent saturated fat—saw a decrease in LDL cholesterol levels, whereas people who consume butter—66 percent saturated fat—saw an increase.

Although contradictory to others, these findings exemplify the complexity of fats and cholesterol.

LDL cholesterol level is seen as the key cardiovascular biomarker, and some believe that higher levels indicate higher rates of disease and mortality. However, in a meta-analysis including 19 studies published in the British Medical Journal (BMJ), researchers found that people with higher LDL cholesterol lived longer than individuals with low or normal LDL cholesterol levels.

“This finding is inconsistent with the cholesterol hypothesis,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Uffe Ravnskov, the study’s main author, told The Epoch Times, “Although our paper has been downloaded by more than a quarter of a million readers, the cholesterol guidelines have not yet been changed.”

Rather than focusing on total LDL cholesterol volume to assess cardiovascular risk, Mr. Bowden said the key to knowing the risk is analyzing the quality of LDL cholesterol.

Depending on the particle size, LDL cholesterol can be big and buoyant or small and dense. Logically, it would make sense that bigger LDL particles present a greater risk. But according to emerging research, the smaller particles can provide a more accurate reading of heart disease risks, he said.

Small and dense LDL particles present a greater risk than big and buoyant ones. (Illustration by The Epoch Times, Shutterstock)

“Even if you have low LDL cholesterol with high LDL particle count, you can have a greater chance of heart disease than someone with cholesterol that is through the roof but has a low LDL particle count,” Mr. Bowden said.

Because particle count isn’t a standard measurement, few doctors utilize its insights.

Smaller LDL particles oxidize more easily and have a lower affinity for LDL receptors in the liver, which, in turn, causes them to float freely in the bloodstream rather than make their way to the liver. Easily oxidized particles without a landing platform such as the liver are what can cause heart damage. This process results in inflammation, which Dr. Roberts said could lead to coronary heart disease.

An eight-year study published in 2020 found that individuals with the highest amount of small, dense LDL particles had a fivefold increased risk of heart disease compared with people with the lowest amount.

In a 2018 study analyzing nearly 28,000 women, researchers found that a high LDL particle count was associated with more than double the risk of peripheral arterial disease, while LDL volume showed no association.

There should be “a reevaluation of guidelines recommending pharmacological reduction of [LDL cholesterol] in the elderly as a component of cardiovascular disease prevention strategies,” wrote the authors of the meta-analysis, which was published in the BMJ.

When Should Statins Be Used?

“Doctors have been trained to rely on the recommendations in the guidelines to determine whether a patient should be taking a statin,” Dr. Abramson said. “But this is a scientifically inappropriate and paternalistic way to approach the decision.

“Patients should be informed by doctors of the actual likelihood that they will benefit from a statin.”

Prescribing statins before a heart attack is called primary prevention. In a 2021 meta-analysis analyzing the effects of statin primary prevention in people aged 50 to 75, researchers found no benefit in mortality rates.

A 2022 review states that the use of statins for primary prevention provides marginal to no benefits and has significant risks, especially among older adults.

“The insistence on prescribing statins is especially perplexing given the multitude of options available to physicians seeking to prevent [cardiovascular disease] in their patients,” wrote the authors of the report, which was published in Atherosclerosis.

However, many doctors still find statins useful for primary prevention, depending on a patient’s risk factors. A low- to moderate-dose generic statin along with ezetimibe—a generic cholesterol absorption inhibitor—“makes sense in some primary care prevention cases,” said Dr. Tom Rifai, a dual board-certified internal and lifestyle medicine specialist and clinical assistant professor of medicine at Wayne State University.

He utilizes the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease Risk Estimator Plus calculator—an assessment designed by the American College of Cardiology—to determine whether to use statins in primary care patients.

Simvastatin (L) (Shutterstock, Getty Images) |  Atorvastatin (R), commonly used statins. |

When statins are prescribed after a heart attack, an extension of mortality has been reported. This is called secondary prevention.

“It’s more clear-cut with secondary prevention patients,” Dr. Rifai told The Epoch Times. “The biggest risk factor for having a heart attack, for instance, is already having had one.”

In his practice, he said, most secondary prevention patients need “at least a modest-dose statin therapy” in addition to lifestyle modifications such as a diet overhaul, increased exercise, and tobacco cessation.

Nevertheless, statins’ overall protective benefits in secondary prevention remain marginal, according to a review published in the British Medical Journal. Using data from 11 studies observing more than 90,000 individuals, researchers found that statins used in secondary prevention postponed death by an average of 4.1 days.

Patients “whose life expectancy is limited or who have adverse effects of treatment” should consider withholding statin therapy, the researchers wrote.

The side effects of statins, coupled with the drugs’ “failure to address the cause of cardiovascular disease,” have steered cardiologist Dr. Jack Wolfson to avoid prescribing them.

“Statins lower LDL, but they do not change outcomes in any significant fashion,” he told The Epoch Times.

Instead, they present a false sense of security that causes individuals to believe that a pharmaceutical drug can resolve a lifestyle problem, according to Dr. Wolfson.

Dr. Abramson noted that the most important cardiovascular risk indicator is whether people follow a healthy lifestyle. Solid scientific evidence shows that people make and maintain healthy changes when enrolled in intensive lifestyle-modification programs.

When people focus first on drug or blood test results to secure heart health, “they are missing the low-hanging fruit; lifestyle determines about 80 percent of the risk,” he said.